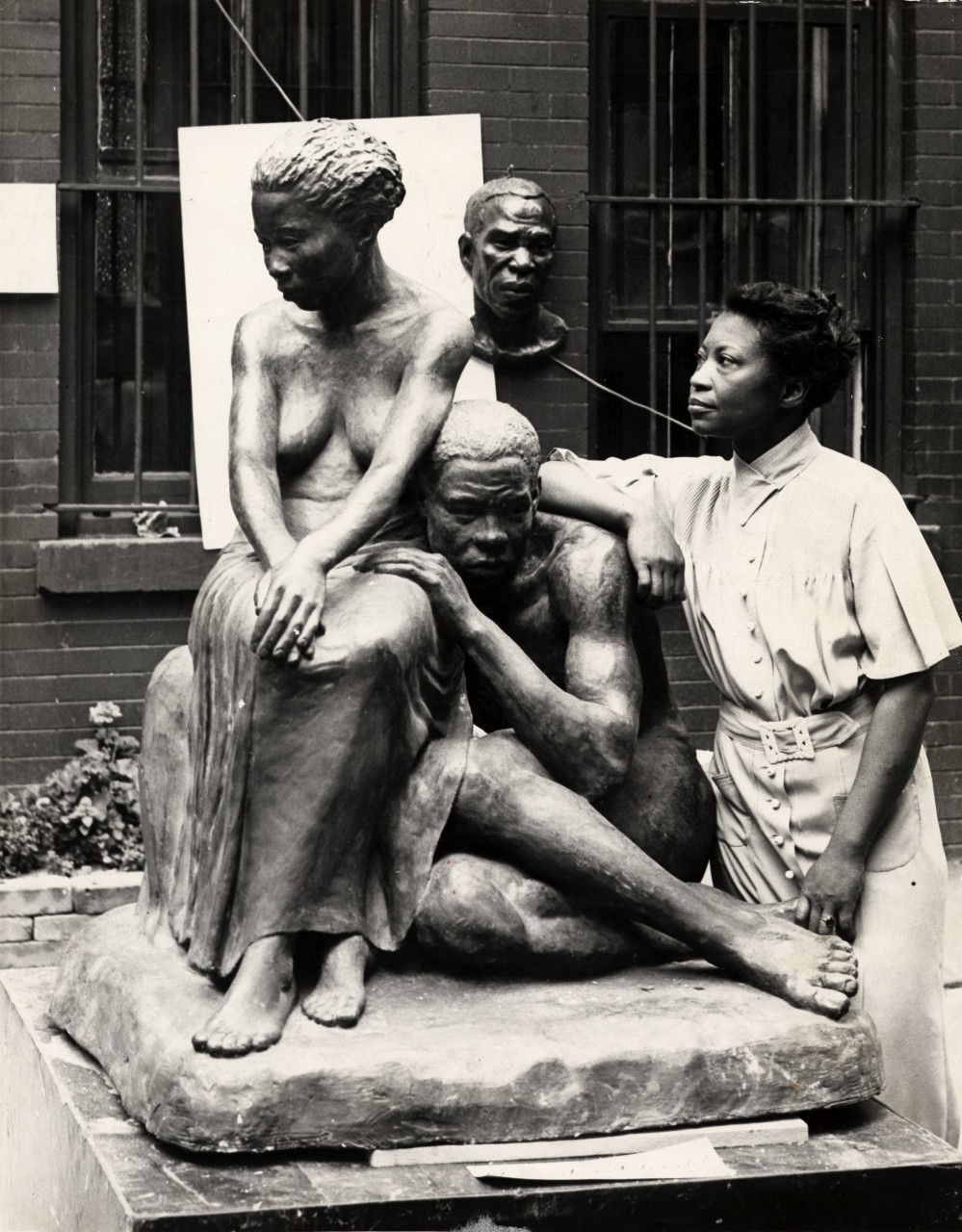

A friend sent me a blog by Keisha A. Blain about the artist Augusta Savage, whose early career flourish with burgeoning arts scene of the Harlem Renaissance when her talents led her to New York. Dr. Blain writes that Savage’s “work was lauded, and she was consistently admired by contemporary black artists, but her renown was transient. And much of her work has been lost”.

Savage was admitted in 1921to Cooper Union [Art School] in New York City. Her talent and ability so impressed the staff and faculty at Cooper, that she was awarded funds for room and board, with tuition being already covered for all Cooper students. She completed her degree in three years.

Blain when on to write that “Savage won a prestigious scholarship at a summer arts program at the Fontainebleau School of the Fine Arts outside of Paris in 1923, but the offer was withdrawn when the school discovered that she was black. Despite her efforts — she filed a complaint with the Ethical Culture Committee — and public outcry from several well-known black leaders at the time, the organizers upheld the decision.

Two years after being rejected from the summer arts program at Fontainebleau, she received a scholarship to study at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Rome, Italy. Unable to raise the funds for travel and living expenses, Savage chose not to accept it. Yet, in some ways, the scholarship itself functioned as validation for her work and evidence of her increasing global visibility and influence in the profession.

During this time she obtained her first commission, for a bust of W. E. B. Du Bois for the Harlem Library. Her outstanding sculpture brought more commissions, including one for a bust of Marcus Garvey. Her bust of William Pickens, Sr., a key figure in the NAACP, earned praise.

Knowledge of Savage’s talent and struggles became widespread in the African-American community; fund-raising efforts provided money for studies abroad. In 1929, Savage enrolled and attended the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, a leading Paris art school. In Paris, she studied with the sculptor Charles Despiau. She exhibited and won awards in two Salons and one Exposition. She toured France, Belgium, and Germany, researching sculpture in cathedrals and museums.

Learn more about August Savage through these links:

The most important black woman sculptor of the 20th century deserves more recognition

and