Nigeria-based artist El Anatsui discusses his large-scale sculpture “< em>Broken Bridge II” New (2012) and the importance of its location on an east-facing wall above the High Line, a relatively new park located on once-abandoned, elevated railroad tracks on Manhattan’s west side, New York City.

By incorporating mirrors into “Broken Bridge II,” a new material for the artist, Anatsui is able to reflect and point out characteristics of New York that he considers iconic. High Line Art’s project manager Jordan Benke and curator Cecilia Alemani discuss the installation process and how this work differs from Anatsui’s smaller sculptures. “Broken Bridge II” will be on view through September 2013. Enjoy seeing this!

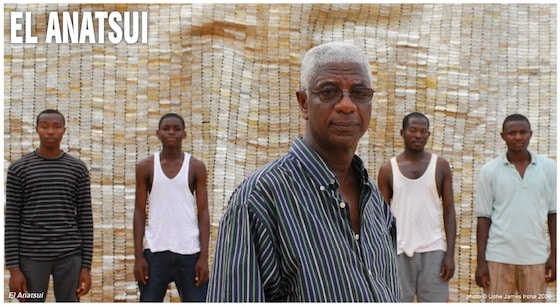

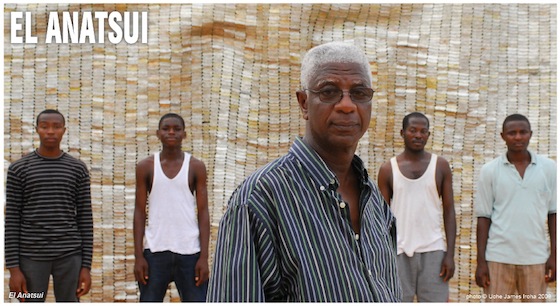

About the artist

El Anatsui was born in Anyako [a town in the Volta Region of Ghana], and trained at the College of Art, University of Science and Technology, in Kumasi, in central Ghana. He began teaching at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, in 1975, and has become affiliated with the Nsukka group.

Working with wood, clay, metal, and the discarded metal caps of liquor bottles, El Anatsui breaks with sculpture’s traditional adherence to forms of fixed shape while visually referencing the history of abstraction in African and European art. Anatsui’s works trace a broader story of colonial and postcolonial economic and cultural exchange, told in the history of cast-off materials, while exploring ideas about the everyday function of objects and the role of language in deciphering visual symbols.

The Nsukka group, known, as a group working to revive the practice of traditional designs of Igbo people of Nigeria (called “ili”) and to incorporate its designs into contemporary art using media such as acrylic paint, tempera, gouache, pen and ink, pastel, oil paint and watercolor. Although traditionally uli artists were female, many of the artists of the group were male. Some were poets and writers in addition to being artists.] Anatsui’s preferred media are clay and wood, which he uses to create objects based on traditional Ghanaian beliefs and other subjects. He has cut wood with chainsaws and blackened it with acetylene torches; more recently, he has turned to installation art. Some of his works resemble woven cloths such as kente cloth. Anatsui also incorporates ili and “nsibidi” into his works alongside Ghanaian motifs.

![[Berlin, Germany] Anatsui’s project, “Who Knows Tomorrow” (2010) work is a large, site-specific sculpture (2010) in the columned vestibule of the Alte Nationalgalerie that is reminiscent of a tapestry. This is mounted directly under the mighty pediment, the cornice of which bears the golden inscription DER DEUTSCHEN KUNST MDCCCLXXI (To the German Art 1871).](https://dsmpublicartfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Anatsui_Installation-in-Germany.jpg)